Tidy First? Daily Empirical Software Design & Why It Works

Contents

Contents

Kent Beck is an American software engineer, the creator of Extreme Programming, an inspiring keynote speaker, and the re-discoverer of Test-Driven Development.

Beetroot was honored to introduce Mr. Beck as a guest speaker for one of our charitable #TechTalk events. Inspired by his vision of software design (because constantly improving the quality of software development runs in our veins), we decided to share some of the key points of the talk with you. Make sure to subscribe to Kent’s blog to get the new chapters of his book as they appear. Buckle up for some exclusive content, folks. Off we go!

About software design

“Software design is an exercise in human relationships.” That was the first line Kent Beck wrote for his upcoming title, Tidy First? At first glance, software development has little to do with social relationships. It is about coupling, cohesion, power laws, refactoring, etc. — the code. But is it? Viewing software design through the prism of human relationships, we can narrow the scope to exploring the interactions between the tech people (geeks) and non-geeks.

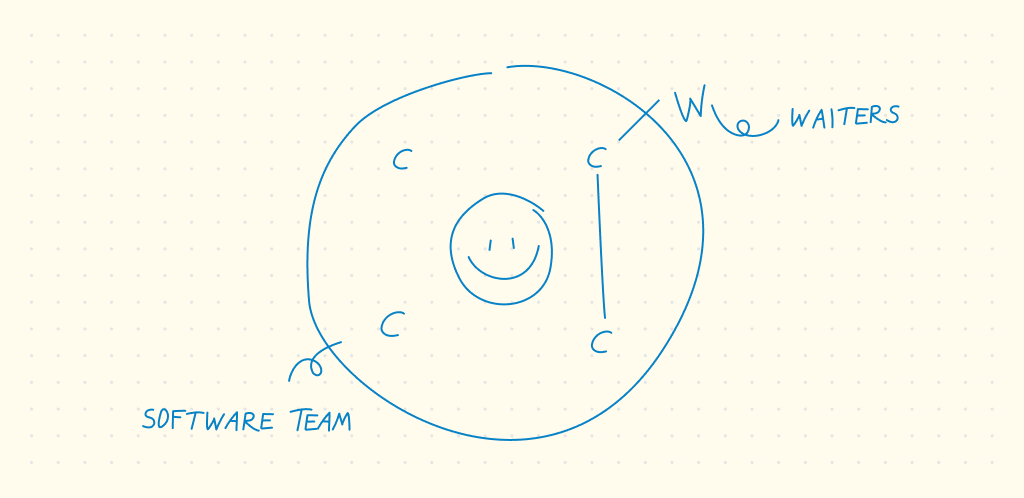

The outer circle on the below scheme draws the line between things geeks can control and things they can’t. Beck calls them “waiters” and “changers.” Waiters request changes to the system’s behavior, while changers actually change the code. Their relationship can be tense, especially when the two sides don’t understand each other. And there is a different set of relationships inside the circle — in a software team where the developers constantly affect each other with their software design decisions.

The third type of relationship is the programmer’s relationship with themselves (hence the happy face in the middle). Poor relationship with ourselves causes us to do the hard job over and over using slow tools or struggling with lousy APIs instead of prioritizing it in the first place and improving all other relationships more effectively. “Until I have a healthy relationship with myself as a programmer, I can’t possibly have healthy relationships even with other programmers,” says Kent Beck. “And this is the foundation, the origins of the scope that I’m talking about today, and the book that I’m writing.”

About tidying

“Here’s the key question: I’m about to change some code, and the structure of the code is such that it’s difficult to change. Should I tidy first?” Beck continues. “I’m not talking about big refactorings. I’m not talking about splitting a monolith into microservices and all these grand and glorious large-scale decisions — I’m talking about my relationship with myself. Am I worth it to make my job easier?” And with that said, programming should not be anxiety-producing and fear-producing, and confidence-ruining. So, taking on a complex problem and breaking it down into smaller things that are easier to understand is an extremely useful habit. “There’s a phrase I came up with almost ten years ago: MCETMEC — Make the Change Easy Then Make the Easy Change. And making the change easy is the province of software design. So rather than go and change some hard, complicated thing where you have to make changes in 100 parts of the system at once, you can tidy first, simplify the cost of making all of those changes, and then make an easy change,” Beck expounds.

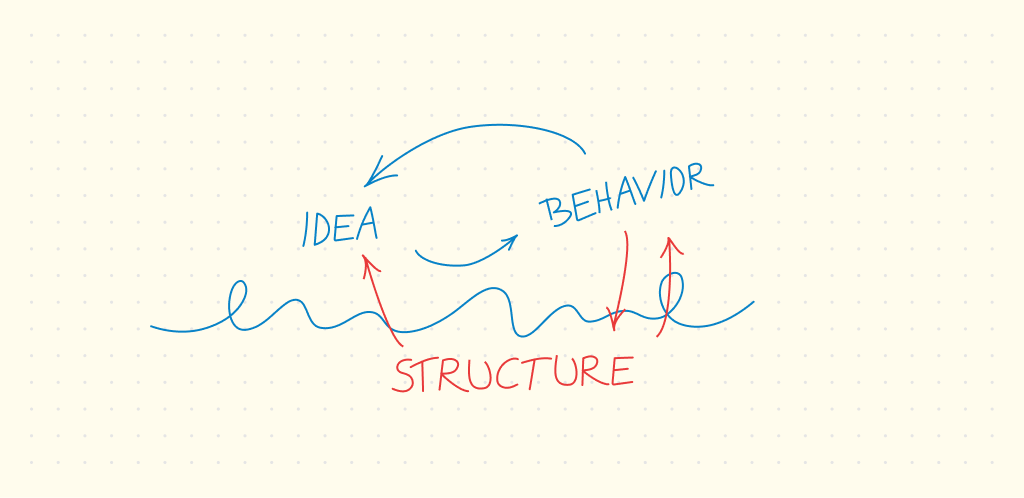

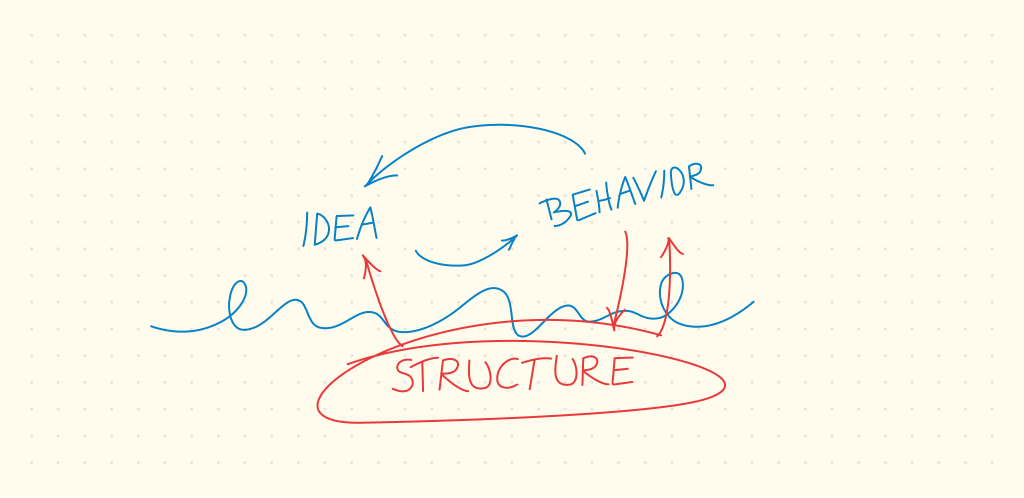

In software development, when we transition from an idea (“I need an edit button”) to change (UX, workflows, and backend behind it), we’re altering the behavior — the externally observable properties of the system. Changing something in the program’s behavior often triggers a cycle where each new feature spawns more features. And there is a parallel track and “under the water part,” which is the structure. One of the magical things here is that the structure can also suggest ideas for what to do about the system. And if you can run all these feedback loops together, you can very quickly explore how your software can create more value.

Now, there can be dysfunctions here. Some development styles focus on the “idea → behavior → idea” loop that creates a hamster wheel of feature implementation without paying attention to the structure.

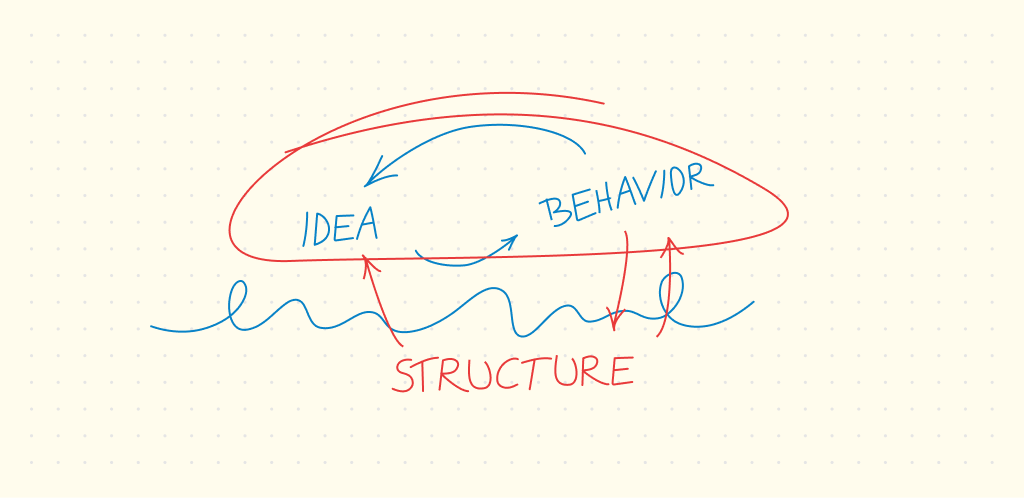

Another dysfunction occurs when all effort goes into perfecting the design before implementing anything (hello, Big Design Upfront!). You get a lot of aesthetically or intellectually pleasing structure that doesn’t actually matter for the behaviors the users care about. You’re making investments with no payoff and only delaying feedback.

At this point, Kent Beck advocates that a rapid iteration should exist in all of the above feedback loops. You should be able to try out ideas quickly, change the structure that is better for the new behavior, and then finish changing the behavior (sometimes, design changes will suggest new ideas for the system and lead you in a new direction). Being able to do all of these activities in tiny slices — that’s what creates superior value.

So, what is tidying?

With his trademark humor, Beck explains, “A tidying is a teensy weensy cute fuzzy little refactoring. It’s a change to the structure that’s gonna make it easier to change the behavior. This tidy-first work attempts to make changing the structure of your code not intimidating.”

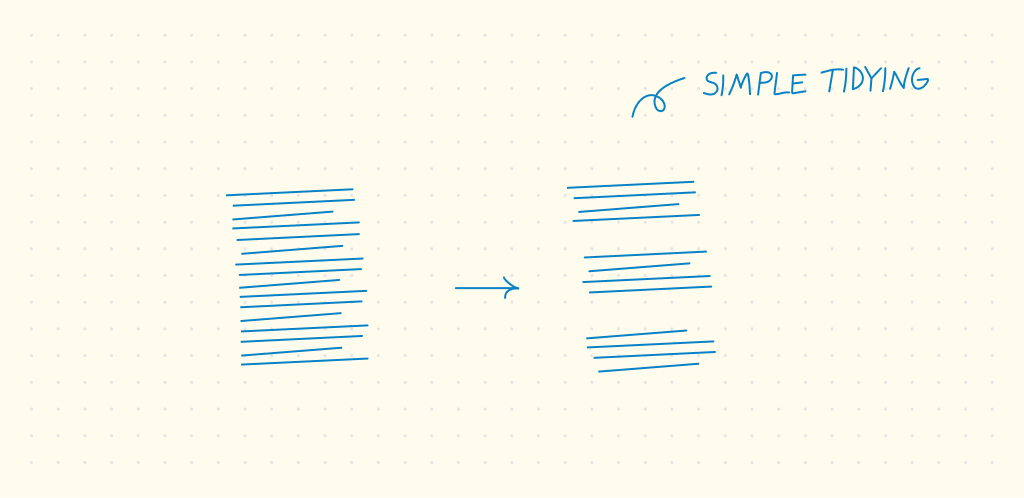

An example. Let’s say you have to deal with a big function containing many lines of code. Before changing it, you read that code to understand what is going on and see how you can logically divide it into smaller chunks.

So, just breaking up code is a simple tidying. We wholeheartedly recommend you to jump to our YouTube channel and watch the full talk to see more examples of tidying using guard clauses, explaining comments, or helping functions.

Why is software expensive to change?

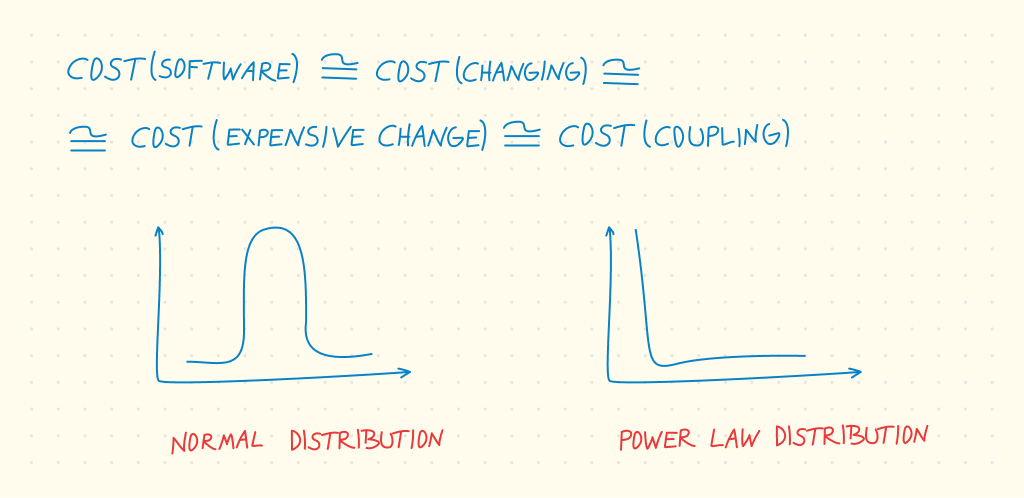

Another insight you can draw from this software design concept is that the cost of software is approximately equal to the cost of changing it, while the initial development is irrelevant. However, not all changes are equal: sometimes, the total cost of making the “cheap” changes is dominated by a few very expensive changes. Technically, the word for the distribution of the cost of features is a power law distribution. Why are some adjustments so much more costly than others then?

We see the same avalanche effect as we saw above, where changing one parameter in a function triggers multiple changes in the system. The relationship between elements that propagates change is coupling. But you also have some decoupling going on. Zooming back out, the role of software design is managing the coupling/decoupling tradeoff: moving too far up either curve makes the cost escalate.

“So finding that minimum between the two, noticing when the coupling is kicked in, noticing that we need to invest, we need to push further on the decoupling cost side to find that minimum — that’s the answer to the question “Should we tidy first?” Kent Beck summarizes, and we can only agree.

Final thoughts

The “tidy first” method addresses the minuscule scale of design changes and returns to the programmers’ relationship with themselves. And that’s a lot to think about to understand the things you can improve to manage your projects and teams better.

That’s why we work towards building a people-centered culture here at Beetroot, where teams can thrive while working in harmony on impactful solutions. We can do many good things together, if you choose one of these teams to support you at any step of your journey.

Subscribe to blog updates

Get the best new articles in your inbox. Get the lastest content first.

Recent articles from our magazine

Contact Us

Find out how we can help extend your tech team for sustainable growth.